Among the first casualties of transgenderism and the ideology it spawned were the sexual and social boundaries of lesbians. But very few know that the problem is far older than this nouveau iteration of what is often referred to as a “culture war.”

In recent years, the exclusivity of on- and offline lesbian spaces have been repeatedly subject to scrutiny from those who clamor for the “inclusion” of trans-identified males. Women who assert their right to keep these spaces single-sex, or who express their attractions as being rooted in sex and not the mystical concept of gender, are met with hostility and branded as bigots.

For example, in 2012, Planned Parenthood of Toronto held a workshop called Overcoming the Cotton Ceiling: Breaking Down Sexual Barriers for Queer Trans Women. The purpose of the workshop was to discuss the “barriers” (cotton underwear) faced by “queer trans women” in “queer women’s communities.” The workshop description also noted that participants would strategize ways to “overcome” these barriers.

The Cotton Ceiling workshop was recently referenced at a court hearing in May. Allison Bailey, a barrister and lesbian activist, took Stonewall and Garden Court Chambers to an employment tribunal for policing her livelihood due to her views on gender ideology. During the course of the hearing, the idea that lesbians must include males in their sexuality was likened to the racial integration of South Africa.

But this was hardly the first time lesbians have been deemed “sexual racists” for not wanting to affirm the identity of males. Nor was it the first time that trans-identified males had attempted to force their way into lesbian communities and lives.

In fact, this is a phenomena goes back decades — right to the beginnings of modern lesbian social and political organizing.

While today’s transgender movement tries to position nebulous conceptions of “gender” over the factual reality and importance of sex, the lesbians of the early gay liberation movement suffered no such confusion. In fact, many who were initially involved in the Gay Liberation Front, which was formed after the 1969 Stonewall Riots, shifted their focus to the growing women’s movement instead. They felt that the gay rights movement was male-dominated and that their interests would be better served by organizing for the specific interests of their own sex.

One of the groups formed by these early lesbian activists was the Radicalesbians. Founded in 1970, the Radicalesbians distributed a manifesto titled “The Woman-Identified Woman” at the Second Congress to Unite Women in New York City. The manifesto focused heavily on the reality of living as a female in a male-dominated society. It helped set the stage for later radical feminist and lesbian feminist thinking.

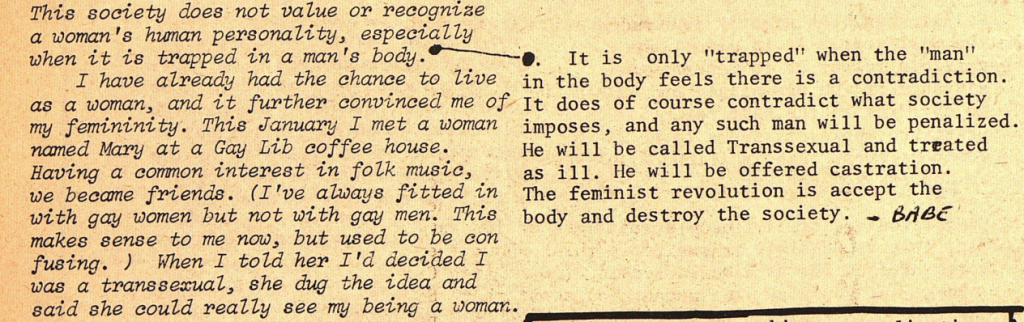

An early example of heterosexual males in the lesbian movement and lesbian lives came later that same year, when folk singer Beth Elliot (Elliott Basil Mattiuzzi) sent a “Letter from a Transsexual” to the radical feminist newspaper It Ain’t Me Babe. “I am a transsexual,” Elliot wrote. “On the intellectual and emotional levels, I know myself to be a woman; on the physical level, my own body denies me this.” Elliot also described how he met and had sex with an “exclusively gay” woman who “could really see my being a woman.”

The editors of the paper invited Elliot to a conversation where they tried to talk him out of undergoing a sex change operation, telling him that it “shouldn’t matter whether one is born with female or male genitalia. That’s our point.” It continues: “As your new reality emerges, as you are able to live it to any degree, you should be able to feel differently about your body.”

Nevertheless, in 1971, Elliot joined and became the vice president of the San Francisco chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis — a lesbian political organization — despite some members’ protestations. He also served as the editor of the group’s newsletter, Sisters. However, accusations of sexual harassment against Elliot in 1972 led to a vote which removed him from the group and barred the inclusion of any trans-identified males in the chapter.

Unable to take a hint, Elliot joined the organizing committee of the West Coast Lesbian Conference in 1973, where he was also slated to perform. On the first night of the conference, a lesbian separatist group called the Gutter Dykes passed out leaflets protesting the presence of a man. Elliot did briefly perform but left soon afterward.

The following day, keynote speaker Robin Morgan amended her address in light of the previous day’s events. Her speech, titled “Lesbianism and Feminism: Synonyms or Contradictions?” contained some strong opinions about referring to men as women.

“No, I will not call a male ‘she,'” Morgan passionately declared, “Thirty-two years of suffering in this androcentric society and of surviving, have earned me the name ‘woman.’ One walk down the street by a male transvestite, five minutes of his being hassled (which he may enjoy), and then he dares, he dares to think he understands our pain? No. In our mothers’ names and in our own, we must not call him sister.”

Morgan’s words rippled through feminist and lesbian communities over the proceeding decade.

By 1977, DYKE magazine had published a six-page feature titled “Can Men Be Women? Some Lesbians Think So! Transsexuals in the Women’s Movement.” The story presented a conversation about some lesbians’ baffling acceptance of men who claim to be same-sex attracted females, like themselves.

Janet, one of the interviewees stated: “That is what is so weird to me, what I find so scary about the way a lot of Lesbians have reacted to the transsexual issue. The attitude seems to be that however someone presents themself, that is the way you are supposed to see them … No distinction is made between respecting someone else and suspending your own perceptions. It is always tempting to be passive.”

Fellow interviewee Liza agreed, writing: “It is also very tempting to be generous. I think that a lot of Lesbians say they have gone through such a hard time being accepted as Lesbians and now these poor transsexuals are having such a hard time and here we are in the same boat, both oppressed by the same culture. If we recognize them as our sisters it helps everybody. It is very generous and I appreciate that in women, but it is really shortsighted.”

It is incredible how the discussions on this topic from more than 30 years ago feel like they could have been plucked from any heated social media page today.

In 1978, the issue was given even greater prominence in the book Gyn/Ecology by Mary Daly, a radical feminist and theologian who taught at Boston College for more than three decades. In a section of her book, “Boundary Violation and the Frankenstein Phenomenon,” Daly opined that “transsexualism is an example of male surgical siring which invades the female world with substitutes.”

Daly was a dissertation advisor for Janice Raymond, who went on to become an even more prominent critic of transsexualism. In 1979, Raymond published The Transsexual Empire: The Making of the She-Male, which highlights many of the issues we are still dealing with. In the book, Raymond argues that transsexualism reinforces gender stereotypes and that it is just another method of patriarchal oppression.

An entire section of the book titled “Sappho by Surgery: The Transsexually Constructed Lesbian-Feminist” deals with the issue of men who claim to be lesbians. Such a man, writes Raymond, “attempts to possess women at a deeper level, this time under the guise of challenging rather than conforming to the role and behavior of stereotyped femininity.”

In a particularly prophetic section, Raymond raises some questions that one could argue reflect the state of the modern lesbian community:

Will the acceptance of transsexually constructed lesbian-feminists who have lost only their outward appendages of physical masculinity lead to the containment and control of lesbian feminists? Will every lesbian-feminist space become a harem?

The only point where Raymond seems to have missed the mark is in the fact that most male lesbians today have not lost their “outward appendage” and, in fact, are very proud of it.

In his book, Transgender History, prominent trans-identified male “lesbian” Susan Stryker helpfully provides us with evidence that Raymond’s ideas were alive and well several years after her book’s publication.

Stryker includes a fiery excerpt from an anonymous 1986 letter to the editor of the San Francisco lesbian newspaper Coming Up:

When an estrogenated man with breasts loves women, that is not lesbianism, that is mutilated perversion. [Such an individual] is not a threat to the lesbian community, he is an outrage to us. He is not a lesbian, he is a mutant man, a self-made freak, a deformity, an insult. He deserves a slap in the face. After that, he deserves to have his body and his mind made well again.

The gay community was still grappling with transsexual (at this point also often referred to as transgender) inclusion during the 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation.

Contrary to the claim of some modern trans activists that the “T” was always part of the acronym, that was not yet the case. The national steering committee of the march did seek to add “transgender” to the title, but it did not receive the necessary majority vote to do so. Over the next few years, however, it became more common for lesbian, gay, and bisexual organizations to include “transgender” in their names and transgender issues in their mandates.

Around this time, another controversy was brewing regarding the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival—often referred to as Michfest—because the predominantly lesbian festival had made clear in 1991 that the event was for “womyn-born womyn,” i.e., females.

This made some males very angry, and they organized an annual demonstration named “Camp Trans” to protest the fact that women had created a female-exclusive entertainment space. Michfest was also criticized by prominent LGBT organizations like GLAAD and the Human Rights Campaign. The festival, which began in 1976, held its final event in 2015 after years of facing increasingly ruthless scrutiny.

The termination of Michfest marked the end of an era, and the beginning of the end in general for lesbian spaces where same-sex attracted women could socialize with one another without the incursion of males.

Lesbian bars were also dying out — not even notoriously-woke Portland had any lesbian bars left by 2016. Identity politics like those that shut down Michfest made it a minefield to create spaces and events that would exclude males who identified as lesbian women. In 2021, Smithsonian Magazine reported that there were only 15 lesbian bars left in the entirety of the United States.

It is now 2022.

Same-sex marriage is legal, and the expectation that homosexual people are free to live their lives is commonplace. Yet, we are facing a new predicament where this generation of lesbians are rapidly losing access to their needed exclusive communities. The music festivals and lesbian conferences once attended by hundreds and even thousands of women are a thing of the past, and any attempt to hold a similar event today would be met with rabid protest.

All of that being said… I do believe there is a silver lining, though it be a somewhat bleak one.

Trans rights activists are becoming increasingly emboldened in their abusive behavior towards lesbians (and all women) that the trickle of criticism seeping through the cracks is inevitably bound to turn into a flood. More and more lesbians are speaking out, joined by feminists and women from all walks of life, and even prominent voices, such as that of Harry Potter author JK Rowling, are joining in to apply pressure.

It might feel sometimes like we are stuck rehashing arguments from the 1970s, but we should be proud to take up the mantle of the women who saw this coming for the benefit of those yet to come.

Reduxx is your independent source of pro-woman, pro-child safeguarding news and commentary. We’re 100% reader-funded! Support our mission by joining our Patreon, or consider making a one-time donation